Tick bites may be prevented by avoiding or reducing time in likely tick habitats and taking precautions while in and when getting out of one.

Tick bites may be prevented by avoiding or reducing time in likely tick habitats and taking precautions while in and when getting out of one.

Most Lyme human infections are caused by bites between April and September. Ticks prefer moist, shaded locations in woodlands, shrubs, tall grasses and leaf litter or wood piles. Tick densities tend to be highest in woodlands, followed by unmaintained edges between woods and lawns, ornamental plants and perennial groundcover, and lawns. Tick larvae and nymphs tend to be abundant also where mice nest, such as stone walls and wood logs.

In the Northeastern United States, 69% of tick bites are estimated to happen in residences, 11% in schools or camps, 9% in parks or recreational areas, 4% at work, 3% while hunting, and 4% in other areas. Activities associated with tick bites around residences include yard work, brush clearing, gardening, playing in the yard, letting into the house pets that roam outside in woody or grassy areas, hiking, or camping.

As a precaution, the CDC recommends soaking or spraying clothes, shoes, and camping gear such as tents, backpacks and sleeping bags with 0.5% permethrin solution and hanging them to dry before use. Permethrin is odorless and safe for humans but highly toxic to ticks. After crawling on permethrin-treated fabric for as few as 10–20 seconds, tick nymphs become irritated and fall off or die. Permethrin-treated closed-toed shoes and socks reduce by 74 times the number of bites from nymphs that make first contact with a shoe of a person. Light-colored clothing may make it easier to see ticks and remove them before they bite. Military and outdoor workers' uniforms treated with permethrin have been found to reduce the number of bite cases by 80–95%. Permethrin protection lasts several weeks of wear and washing in customer-treated items and up to 70 washings for factory-treated items. Permethrin should not be used on human skin, underwear, or cats.

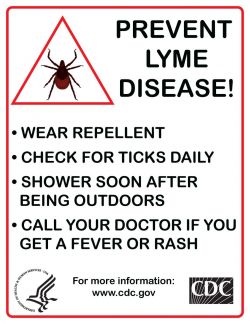

The EPA recommends several tick repellents for use on exposed skin, including DEET, picaridin, IR3535 (a derivative of amino acid beta-alanine), and oil of lemon eucalyptus and its active ingredient para-menthane-diol. Unlike permethrin, repellents repel but do not kill ticks, protect for only several hours after application, and may be washed off by sweat or water. Unlike DEET, picaridin is odorless and is less likely to irritate the skin or harm fabric or plastics. Repellents with higher concentration may last longer but are not more effective; against ticks, 20% picaridin may work for 8 hours vs. 55–98.11% DEET for 5–6 hours or 30–40% OLE for 6 hours. Repellents should not be used under clothes, on eyes, mouth, wounds, or cuts, or on babies younger than 2 months (3 years for OLE or PMD). If sunscreen is used, repellent should be applied on top of it. Repellents should not be sprayed directly on a face but should instead be sprayed on a hand and then rubbed on the face.

After coming indoors, clothes, gear and pets should be checked for ticks. Clothes can be put into a hot dryer for 10 minutes to kill ticks (just washing or warm dryer are not enough). Showering as soon as possible, looking for ticks over the entire body, and removing them reduce risk of infection. Unfed tick nymphs are the size of a poppy seed, but a day or two after biting and attaching themselves to a person, they look like a small blood blister. The following areas should be checked especially carefully: armpits, between legs, back of knee, bellybutton, trunk, and in children’s ears, neck and hair.

Attached ticks should be removed promptly. The risk of infection increases with time of attachment, but in North America the risk of Lyme disease is small if the tick is removed within 36 hours. The CDC recommends inserting a fine-tipped tweezer between the skin and the tick, grasping very firmly, and pulling the closed tweezer straight away from the skin without twisting, jerking, squeezing, or crushing the tick. After tick removal, any tick parts remaining in the skin should be removed with the tweezer, if possible. The wound and hands should then be cleaned with alcohol or soap and water. The tick may be disposed by placing it in a container with alcohol, sealed bag, tape or flushed down the toilet. The bitten person should write down where and when the bite happened so that this can be informed to a doctor if the person gets a rash or flu-like symptoms in the following several weeks. The CDC recommends not using fingers, nail polish, petroleum jelly or heat on the tick to try to remove it.

The risk of infectious transmission increases with the duration of tick attachment. It requires between 36 and 48 hours of attachment for the bacteria that causes Lyme to travel from within the tick into its saliva. If a deer tick that is sufficiently likely to be carrying Borrelia is found attached to a person and removed, and if the tick has been attached for 36 hours or is engorged, a single dose of doxycycline administered within the 72 hours after removal may reduce the risk of Lyme disease.

Several landscaping practices may reduce the risk of tick bites in residential yards. The lawn should be kept mowed, leaf litter and weeds removed, and groundcover use avoided. Woodlands, shrubs, stone walls, and wood piles should be separated from the lawn by a 3-ft-wide rock or woodchip barrier. Without vegetation on the barrier, ticks will tend not to cross it. Acaricides may also be sprayed on it to kill ticks. A sun-exposed tick-safe zone at least 9 ft from the barrier should concentrate human activity on the yard, including any patios, playgrounds, and gardening. Materials such as wood decking, concrete, bricks, gravel, or woodchips may be used on the ground under patios and playgrounds so as to discourage ticks there.

A recombinant vaccine against Lyme disease, based on the outer surface protein A (ospA) of B. burgdorferi, was developed by SmithKline Beecham. In clinical trials involving more than 10,000 people, the vaccine, called LYMErix, was found to confer protective immunity to Borrelia in 76% of adults and 100% of children with only mild or moderate and transient adverse effects. LYMErix was approved on the basis of these trials by the FDA in 1998.

Following approval, use of the vaccine was slow for a variety of reasons, including its cost, which was often not reimbursed by insurance companies. Subsequently, hundreds of vaccine recipients reported they had developed autoimmune and other side effects. Several class action suits were filed against GlaxoSmithKline, alleging that the vaccine had caused these health problems. These claims were investigated by the FDA and the CDC, which found no connection between the vaccine and the autoimmune complaints.

However, sales of the vaccine decreased, and it was withdrawn from the US market by GSK in February 2002, in the setting of negative media coverage and fears of vaccine side effects.

Sources: CDC, FDA, MSN.com